Hungry nation, wasteful plate: Bangladeshis waste more food than China, India, UK

- Update Time : Sunday, November 9, 2025

TDS Desk:

The plates gleam beneath chandelier light. Aromas of roasted meat, saffron rice and butter-soaked naan fill the air. Guests laugh, snap photos and move from buffet line to buffet line, piling their plates high – yet by the end of the night, the bins behind the glittering banquet hall overflow. Half of the food will never be eaten.

In another corner of Dhaka, under the same November sky, a mother waits in line outside a roadside stall for leftover rice. She clutches a plastic container and hopes there will be enough to feed her two children that night.

Two worlds, two realities – in one country.

Bangladesh, still ranked among the “moderate hunger” nations in the Global Hunger Index, is living a cruel paradox. It is a nation that feeds waste, even as hunger stalks its people.

A GROWING APPETITE FOR WASTE

Restaurant owners say that around 20 per cent of food is wasted every day in the country’s elite eateries. In buffet-style restaurants – now a symbol of luxury dining – half of what customers take ends up in the bin.

“Every day I see plates come back half full,” said Imran Hasan, Secretary General of the Bangladesh Restaurant Owners Association. “It’s not that the food is bad – people just take more than they can eat. This culture of waste is becoming frightening, especially in affluent neighbourhoods and tourist areas.”

The picture is even worse in community centres and wedding halls. “At events, one-third of the food is wasted,” said Sajjadur Rahman, owner of an elite community centre in Dhaka. “Guests eat a little, talk a lot and leave their plates full. The leftovers can fill trucks. Sometimes I think if this food reached the poor, no one would sleep hungry.”

But it doesn’t. Most of it goes straight to landfill sites, where it rots alongside plastic and rubbish – a symbol of how abundance and hunger coexist in the same breath in Bangladesh.

THE NATION THAT PRODUCES YET FAILS TO FEED

Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in food production. From rice to fish to fruit, the country grows more food today than ever before. But it fails to preserve it.

A joint World Bank–CPD study found that 34 per cent of all food produced in Bangladesh is wasted every year. That’s one-third of what the nation grows – lost to mismanagement, poor transport and neglect.

Economically, it’s devastating. The value of this wasted food equals 4 per cent of the country’s GDP. Environmentally, it’s disastrous – about 34,000 square kilometres of farmland produce food that will never be eaten.

And morally, it’s heartbreaking.

“We are increasing agricultural production,” said Dr Mirza Mofazzal Islam, former Director General of the Bangladesh Institute of Nuclear Agriculture, “but food security is not increasing. We produce more – yet more goes to waste. We are growing to throw away.”

NUMBERS THAT SHAME US

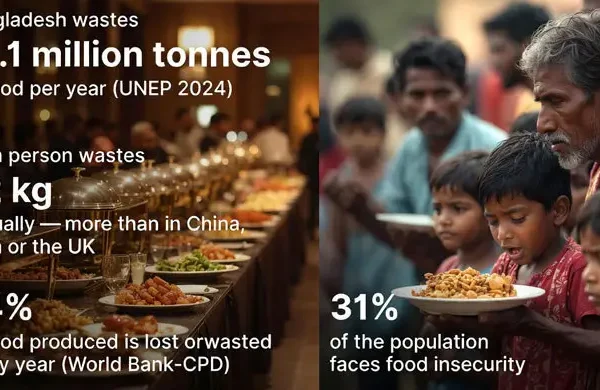

In 2024, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) reported that Bangladesh wastes 14.1 million tonnes of food every year – up by a third from its 2021 report. On average, every Bangladeshi wastes 82 kilograms of food per year.

That’s more than what people waste in China (75 kg), India (55 kg) or the UK (76 kg).

Behind these cold numbers lies a tragic irony. Bangladesh is home to 31 per cent of people who suffer from food insecurity, and 66 per cent of the population lacks access to nutritious food. Yet the nation is wasting more food than some of the wealthiest countries in the world.

TWO FACES OF WASTE

Experts divide the country’s food waste into two categories – both equally alarming.

POST-HARVEST LOSS:

This happens when food is lost before it ever reaches the market – during production, transport or storage. In Bangladesh’s hot, humid climate, where preservation technology is outdated, food spoilage is rampant.

A study revealed that every year, 23 per cent of rice, 27 per cent of lentils, 36 per cent of fish, and 29 per cent of mangoes produced in Bangladesh are wasted – highlighting the scale of inefficiency and loss across key food categories that are central to the nation’s diet and economy.

Vegetables and fruit fare no better – 25-30 per cent of bananas, papayas and guavas never make it to consumers.

“From field to fork, our food system leaks everywhere,” said Dr Jahangir Alam, an agricultural economist. “Farmers lose crops to pests, markets lose food to heat, and households lose food to carelessness. It’s a broken circle.”

CONSUMER WASTE:

The other face of waste is the one we see every day – food left uneaten in homes, restaurants and events. This, experts say, is rising fast.

“There’s a kind of ‘unjust luxury’ in our food culture now,” said Hasan. “People want to show abundance. It’s become fashionable to waste.”

STORIES FROM TWO ENDS

In Dhaka’s upmarket neighbourhoods, buffet restaurants boast endless options – eight types of kebab, five desserts, imported cheeses. A family of four often leaves behind enough uneaten food to feed another family.

Meanwhile, in the northern Kurigram district, families skip meals during the lean season. Mothers serve their children just boiled rice with salt.

The distance between these realities isn’t measured in kilometres – it’s measured in awareness.

“We’ve turned food into a form of entertainment,” said Sajjadur Rahman. “At weddings, people don’t think about what happens to the food afterwards. There’s no shame in waste anymore.”

In the outskirts of the capital, volunteers from small NGOs sometimes collect leftovers from hotels and distribute them to slum dwellers. But such initiatives are rare and inconsistent.

“We’ve tried to collect restaurant leftovers, but hygiene laws make it complicated,” said one volunteer. “And honestly, some owners don’t care enough to bother.”

A GLOBAL PROBLEM, A LOCAL CRISIS

Food waste is a global issue, but its consequences hit developing countries hardest. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), one-third of all food produced worldwide is wasted – while 783 million people go hungry.

In Bangladesh, food waste isn’t just a moral issue – it’s economic, environmental and human. Wasted food means wasted water, wasted energy, wasted land and wasted labour. It also means more methane emissions from rotting waste – contributing to climate change.

“We are losing on every front,” said Dr Alam. “Wasting food is like throwing away hope – the hope of a farmer, a child, a country.”

THE MISSING LAW

While countries like France and Italy impose fines for food waste, Bangladesh has no such policy.

“There should be a law against it,” argued Imran Hasan. “In some countries, restaurants must donate unsold food to charities. Why can’t we do that?”

But Zakaria, Director General of the Bangladesh Safe Food Authority, admits that no legislative steps have been taken yet. “We don’t have enough data to act,” he said. “The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics is working on it. Once we have the numbers, we’ll consider steps. For now, we’re running awareness campaigns.”

Awareness alone, however, may not be enough.

TOWARDS A CONSCIOUS PLATE

Experts and activists agree that preventing food waste starts with awareness – but must end in accountability.

Restaurants can offer smaller portion options or donate excess food safely.

Households can buy only what they need and store food properly.

Event organisers can plan menus responsibly and redistribute leftovers.

The government can establish laws, tax incentives and food banks.

At the same time, investment in cold storage and transport infrastructure could save millions of tonnes of produce every year.

“Reducing waste is not just about saving food,” said Dr Mofazzal Islam. “It’s about respecting the effort that goes into every grain — from the farmer’s sweat to the mother’s prayer at the table.”

BETWEEN HUNGER AND LUXURY

Every wasted plate tells a story of contrast. The half-eaten biryani at a wedding; the rotting mangoes in a truck stuck in summer traffic; the unsold vegetables dumped by farmers; the empty bowls of children in northern villages.

Bangladesh has come a long way from famine to self-sufficiency — yet it risks losing that victory to its own carelessness.

The future depends on whether the nation learns to balance abundance with empathy, and production with preservation.

The next time a plate is filled to the brim at a buffet or a dinner party, perhaps it’s worth remembering: somewhere, someone is waiting for that same food — not as luxury, but as life.

Because in a land still haunted by hunger, the greatest tragedy is not that there isn’t enough food – it’s that there’s too much wasted.