34 years of Ershad’s fall: Bangladesh with another chance for democracy

- Update Time : Friday, December 6, 2024

TDS Desk

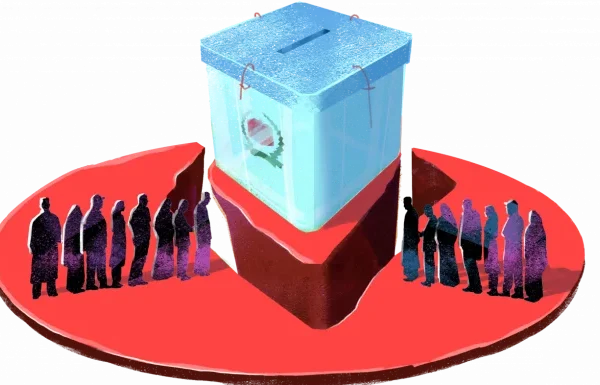

Bangladesh has always had a rocky, and often contentious, relationship with democracy.

Just four years after gaining independence, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman introduced a one-party rule by forming the BAKSAL and switching to a presidential system.

Following his assassination, the country witnessed a series of coups, counter-coups, military rule and authoritarian regimes.

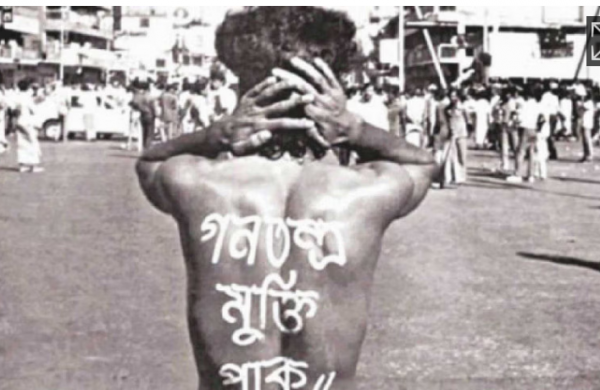

In the first half of 1980s, students—later followed by political parties—took to the streets against military dictator HM Ershad. This was the beginning of a collective quest for democracy. As protests intensified and turned into a mass uprising, Ershad was compelled to hand over power on December 6, 1990, exactly 34 years ago.

Ershad’s fall was a significant turning point in Bangladesh’s political history, ushering in hope among the people that they would finally be able to build a democratic nation.

One key source of this hope was a compact of three alliances, united in their mission to oust Ershad through a rare political consensus.

At the final stage of the anti-Ershad protests, on November 21, 1990, an eight-party alliance led by the Awami League (formerly a 15-party alliance), a seven-party alliance led by the BNP, and a five-party leftist alliance came together to sign the “Tin Joter Ruprekha” (roughly translated to the Tri-alliance Outline).

The declaration stated that people from all walks of life participated in the campaign to remove Ershad and establish a permanent democratic order. Throughout this struggle, people sacrificed their lives for the establishment of a truly representative government.

The joint declaration also called for the protection of fundamental rights, the independence of the judiciary, the establishment of rule of law, and government accountability to parliament.

The journey towards democracy began fairly satisfactorily.

The BNP won the 1991 parliamentary elections under an interim government, considered perhaps the most widely accepted national election in Bangladesh. Later that year, the country transitioned to a parliamentary democracy from a presidential system.

However, the hopes of the people for true democracy were dashed in the following years.

The caretaker government issue became contentious, leading to repeated political crises. The BNP adopted the system only after strong street protests led by the Awami League in 1996.

Once again, the country was in a political crisis in 2007–2008 when a military-controlled caretaker government had to take the helm. This crisis was triggered by disputes over who would lead the caretaker government in 2006. Two years after taking power, the Awami League abolished the caretaker government system in 2011, ignoring the opposition’s demands.

The Sheikh Hasina-led government has been accused of depriving citizens of their right to vote, in the elections of 2014, 2018, and 2024, all held under a political government.

Amid these developments, the parliament has weakened and failed to hold the executive branch accountable. Opposition boycotts, the use of unparliamentary and abusive language, verbal attacks on opposition leaders, and narcissistic self-adulation have become common in the House.

In the last three parliaments, there has been virtually no opposition. Laws have been passed to restrict the media, curtail freedom of speech, and suppress dissenting voices, including those of opposition leaders.

Meanwhile, businessmen have increasingly dominated politics and parliament. The criminalisation of politics has escalated, with politicians amassing fortunes through corruption and siphoning billions of dollars in collusion with opportunist businessmen.

Between 2009 and 2023, an estimated Tk 25,74,000 crores was reportedly siphoned off from Bangladesh under the Awami League regime, according to the white paper on the state of the economy.

The head of the white paper committee stated that the country had transformed Bangladesh from “crony capitalism” into a “kleptocracy” under Awami League rule. The roots of this kleptocracy can be traced back to the last three elections.

In 1991, the interim government had established 29 task forces which made valuable recommendations for reforms in various sectors. Unfortunately, subsequent governments ignored them.

The caretaker government in 2007–08 also talked about reforms in different sectors, but almost all fell by the wayside.

Against this backdrop, Bangladesh stands poised on the edge of transformative change, teetering between promise and peril. Amid this uncertainty, the interim government led by Professor Muhammad Yunus—following the student-led mass uprising that toppled the autocrat regime of Sheikh Hasina—has emerged to symbolise people’s hopes and aspirations.

This government has promised reforms to strengthen democratic institutions, which the Awami League systematically dismantled and destroyed. The incumbent has promised to establish a state system rooted in public ownership, accountability and welfare, and lead the country towards a genuine democracy.

Bangladesh stands at a critical juncture. It has been presented with yet another opportunity to forge a national consensus to steer the nation toward true democracy. We lost the first opportunity soon after independence and the second chance following Ershad’s fall.

The country cannot afford to squander the same opportunity a third time.