October 1958: Iskandar Mirza and Ayub Khan

- Update Time : Monday, October 7, 2024

—Syed Badrul Ahsan—

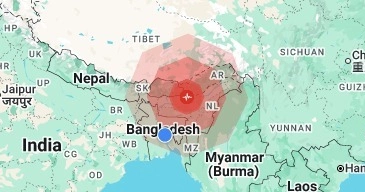

On 7 October 1958, the state of Pakistan was pushed down the road to political disaster. In a move that was as unseemly as it was foolhardy, Major General Iskandar Mirza, President of Pakistan, imposed martial law on the country, abrogated the constitution and dissolved parliament. A ban was clamped on all political parties. These moves were followed by the arrest of a large number of politicians in both East and West Pakistan.

President Mirza was not alone in his decision to take that extreme step. He was in cahoots with General Mohammad Ayub Khan, the commander-in-chief of the Pakistan army, in the plan to send democratic politics packing. As Ayub would make it known in his memoirs years later, his ambition of seizing power had become part of his political psychology in 1954, a time when he served both as chief of the army and minister of defence. Both Mirza and Ayub held politicians, all of whom had been involved in the struggle for the creation of Pakistan, in deep contempt.

The very first general elections in Pakistan were expected in early 1959, an exercise which would certainly have given the country an opportunity to join the club of such democratic nations as neighbouring India. Ayub and Mirza, both with a hunger for power, were unwilling to have politicians run the show. It did not matter that Pakistan’s politicians, among whom were Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Chaudhry Mohammad Ali, Ayub Khuhro and others, had finally managed to give Pakistan a constitution in 1956, nine years after the country came into being.

General Mirza, who had earlier replaced the equally ambitious but ailing Ghulam Mohammad as Governor General, was sworn in as President under the 1956 constitution. The constitution set in place a parliamentary form of government for Pakistan in line with the Westminster tradition. The expectation was that the constitution would inaugurate a healthy democratic system in the country. On 7 October 1958, President Mirza brazenly violated the very constitution on the basis of which he had become President and so torpedoed the years-long efforts of Pakistan’s political leaders to set the country on the road to democratic governance.

Mirza’s next move after the imposition of martial law was to appoint General Ayub Khan as Chief Martial Law Administrator. The irony, again, was that Mirza did not realise that by placing Ayub in that powerful position he was sacrificing his own future. Both Mirza and Ayub were wily in character but in the end the shrewd Ayub emerged triumphant. Prior to that, Mirza formed a cabinet into which was inducted a young foreign-educated lawyer from Larkana named Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. The young minister, a friend of Mirza’s son Humayun Mirza, was so overwhelmed at being appointed to the cabinet that he dashed off a letter to Mirza effusively thanking him and, wonder of wonders, informing Mirza that history would remember the President as a man greater than Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of the country.

The twenty days which followed the declaration of martial law were spent impatiently by Ayub Khan, who was clearly uncomfortable at having to share power with Mirza. For his part, Mirza remained blissfully unaware of the intrigue Ayub and his fellow officers were shaping against him in the army. Generals Burki, KM Sheikh, Musa, Yahya Khan and others, loyal to their chief, were convinced that a dichotomy of power was untenable and that President Mirza would have to go. On 27 October, some of these officers, among whom was Yahya, were sent to Mirza at the latter’s official residence in Karachi, Pakistan’s capital at the time, and forced to resign at gunpoint. Mirza and his second wife Naheed (who had earlier been married to an Iranian naval attache at Tehran’s embassy in Pakistan) were flown to Quetta. A few days later, they were sent into exile in London. Mirza would never be permitted to return to Pakistan.

On 27 October, undiluted power came into Ayub Khan’s hands. He was now not only Chief Martial Law Administrator but also President of Pakistan. He formed a cabinet comprised largely of military officers but including some civilians. The young Bhutto had a quick somersault, changing loyalties to convince Ayub that he was happy to be part of the general’s team. It was an early hint of the ambition that would define Bhutto’s politics in the years ahead. Meanwhile, the imposition of martial law and Ayub’s seizure of power were given questionable legal validity by the higher judiciary, headed by Justice Mohammad Munir, through what it referred to as the Doctrine of Necessity. In subsequent years, it was this controversial step that would allow ambitious soldiers to play havoc with politics in both Pakistan and Bangladesh. Munir was the same man under whom Pakistan’s chief court, on the basis of the Doctrine of Necessity, rejected Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan’s legal challenge to the dismissal of the Constituent Assembly by Governor General Ghulam Mohammad in 1954. Four years later, Munir was up to his old tricks again. He compared Ayub’s takeover as a revolution comparable to the French and Russian revolutions, which it certainly was not.

The imposition of martial law on 7 October by Iskandar Mirza and Ayub Khan was a harbinger of the unending tragedy which would unfold in Pakistan. Mirza, in exile in London, ended up being the manager of a restaurant and yet dreaming of a return to his country. Meanwhile, Ayub Khan took Pakistan to be his experimental laboratory. His regime put in place the notorious Elective Bodies Disqualification Ordinance (EBDO) in 1959, a move aimed at forcing politicians out of politics. The general, who soon appointed himself field marshal without demonstrating valour in any war, ruled Pakistan for the first four years under martial law.

Not until a new constitution was framed by the regime in 1962 — and it was a document which sought to entrench the military in power through discarding adult franchise in favour of an electoral college of a mere 80,000 members — was martial law lifted.

But the end of martial law did not mean an inauguration of democratic politics. Ayub was to be a dictator for all the ten years he held power. Pakistan was given a National Assembly and two Provincial Assemblies (in East and West Pakistan) whose members were chosen by the 80,000 individuals called Basic Democrats. President Ayub Khan retained the authority to appoint governors, a result of which was the appointment and dismissal of such East Pakistan governors as General Azam Khan and Ghulam Faruque. An obscure Bengali lawyer and Ayub loyalist named Abdul Monem Khan would serve as Governor of East Pakistan between 1962 and 1969. In West Pakistan, the powerful Nawab of Kalabagh, Malik Amir Mohammad Khan, would be Governor for a number of years until he was replaced by General Mohammad Musa, who had by then retired from his position of army chief. The Nawab would subsequently be murdered by one of his sons in what was given out as a family feud. Ayub Khan successfully broke up the Muslim League, walking away with a faction which would be known as the Convention Muslim League, in his bid to don the garb of a civilian politician.

In his decade in power, Ayub presided over the creation of a civilian-military complex which cheerfully undermined politics and prevented the growth of a democratic culture in Pakistan. Sycophants in the civil service and the media demonstrated their love for the dictator in ways that were embarrassing. Ayub had his memoirs ‘Friends Not Masters’, ghost-written. In 1965, he and Bhutto, who had become Foreign Minister after the death of Mohammad Ali Bogra in 1963, led the country to a pointless war with India, an exercise which forced the regime into initialling the Tashkent Declaration with Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri in January 1966. The ambitious Bhutto, disseminating misleading information about a ‘secret clause’ in the declaration, was soon out of the government, intent on initiating a campaign against his benefactor. In East Pakistan, Ayub Khan expended all his energies in trying to destroy the rising Bengali nationalist leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The Agartala Conspiracy Case, initiated to end Mujib’s career, ironically ended up finishing Ayub Khan.

Ayub Khan’s admirers were fond of ascribing to him the qualities of what they called an Asian Charles de Gaulle. His years in power were celebrated as a decade in development. However, the celebrations coincided with the gathering movement against his dictatorship in both wings of the country. By early 1969, he was in deep trouble. Forced to withdraw the Agartala Case, he welcomed his nemesis Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to a round table conference in Rawalpindi. Having earlier arrested Khan Abdul Wali Khan and Bhutto, he was eventually forced to free them.

Ayub Khan’s departure from power in March 1969 was a final undemocratic move on his part. He did not hand over the presidency, as envisaged under his 1962 constitution, to Abdul Jabbar Khan, the Speaker of the National Assembly, but to General Yahya Khan, the army commander-in-chief. Yahya promptly placed Pakistan under a new martial law.

The damage that Iskandar Mirza and Ayub Khan did to Pakistan is part of history. Ayub died forgotten and unlamented in April 1974. Iskandar Mirza passed away in London in November 1969. Yahya Khan did not agree to his burial in Pakistan, which forced his family to have him interred in Tehran.

____________________________________

Syed Badrul Ahsan writes on politics.