Agricultural insurance programme: A New Dawn for Bangladesh’s Agri sector?

- Update Time : Friday, November 15, 2024

–H. M. Nazmul Alam–

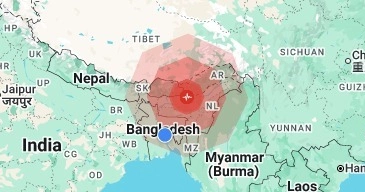

Agriculture, the bedrock of Bangladesh’s economy, has historically supported millions of households, shaped rural communities, and nourished the population. Despite its immense role, the agricultural sector has long been plagued by neglect, climate vulnerability, and economic challenges. Against this backdrop, Tarique Rahman and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) have introduced a bold vision to reinvigorate Bangladesh’s agricultural landscape. As we examine this ambitious plan, we must consider both its transformative potential and the practical challenges it may face.

One of the foundations of Tarique Rahman’s vision is a nationwide agricultural insurance programme. Crop insurance is a timely intervention given the growing impact of climate change on Bangladesh’s predominantly rural communities. In a country frequently struck by floods, cyclones, and other natural disasters, insurance could offer a safety net, shielding farmers from debt and poverty cycles. Similar initiatives have proven effective elsewhere; for instance, India’s Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) offers coverage to over 50 million farmers, cushioning them against crop losses and motivating them to reinvest in their fields.

Rahman’s vision would similarly provide insurance for small and medium-sized farmers in Bangladesh, helping them withstand crop failures due to floods, droughts, and storms. As Norman Borlaug, the renowned agriculturist and “father of the Green Revolution,” famously said, “Food is the moral right of all who are born into this world.” Rahman’s proposal to protect farmers with insurance aligns with this idea, recognising that agriculture should be a source of stability, not volatility.

Another significant aspect of Rahman’s vision is the revival of Bangladesh’s canal-digging initiative, which had been previously undertaken during Ziaur Rahman’s tenure. This programme will address a fundamental need — water. In recent decades, Bangladesh’s water level has dropped alarmingly, threatening agricultural productivity. Rahman’s canal programme aims to harness monsoon rains, channeling them into reservoirs and providing much-needed irrigation during dry seasons. This idea reverberates with China’s water management practices, where advanced irrigation and water recycling have transformed arid land into productive farmland.

A related and essential aspect of this vision is efficient water management. Agriculture accounts for 90% of Bangladesh’s freshwater use, yet most farmers lack knowledge of optimal irrigation techniques. Rahman’s vision emphasises educating farmers on the importance of controlled water usage to prevent wastage and enhance crop resilience. Rahman’s approach advocates for sensible water management practices, but the challenge lies in execution. Effective farmer education programmes could help spread knowledge and ensure these techniques are adopted on a wide scale.

Another innovative proposal is Rahman’s idea to establish crop-specific cold storage facilities in key agricultural zones. Every year, significant portions of Bangladesh’s perishable crops — especially vegetables like onions, potatoes, and tomatoes — are lost due to inadequate storage facilities. This loss not only reduces farmers’ incomes but also destabilises market prices. By creating a cold storage network, Bangladesh could follow in the footsteps of countries like the Netherlands, where robust storage infrastructure supports food security and enables exports. If Bangladesh could harness its own cold storage infrastructure, it might stabilise prices, reduce imports, and even consider exporting select produces, contributing to economic resilience.

Cold storage facilities are only one part of Rahman’s broader vision to diversify Bangladeshi agriculture. A diversified agricultural system could strengthen Bangladesh’s food self-sufficiency, reducing reliance on imports and building resilience against market fluctuations. The United States’ “Farm to Fork” strategy is an example of agricultural diversity bolstering food security, enabling the U.S. to be a net food exporter. If Rahman’s plan for agricultural diversification takes hold, Bangladesh might similarly boost both food security and economic opportunity for rural communities.

Perhaps the most revolutionary element in Rahman’s plan is his proposal for fair crop pricing. He envisions government procurement centres at the union level, designed to eliminate middlemen and ensure farmers receive fair value for their produces. This model echoes India’s Minimum Support Price (MSP) system, which safeguards farmers against price volatility.

Finally, Rahman’s ambition to increase the national agricultural budget to 8% of GDP demonstrates a commitment to long-term investment. This funding would be directed towards improving access to fertilisers, farm machinery, and training programmes, especially for small and medium-sized farmers.

While Rahman’s vision presents a promising framework, it also raises critical questions about execution. Agricultural reform is complex, requiring not only well-crafted policies but also strong administrative capacity. Implementing these ambitious changes would require close collaboration between government agencies, local communities, and private partners. Corruption, inefficiency, and bureaucratic delays remain significant obstacles. Rahman’s approach, though innovative, will need to account for these administrative challenges.

____________________________________

The writer is Lecturer, Department of English and Modern Languages, International University of Business, Agriculture and Technology.