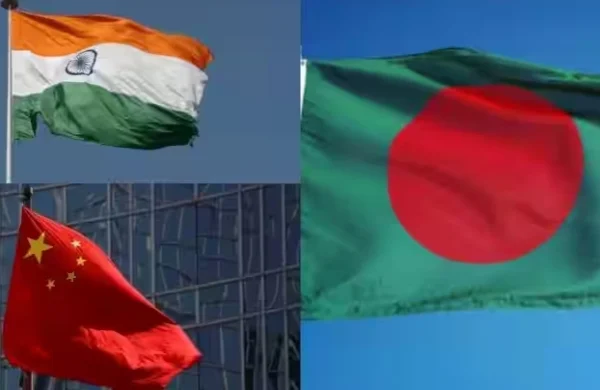

BD looks on as China, India move to have Brahmaputra in chokeholds

- Update Time : Friday, August 22, 2025

TDS Desk:

Bangladesh looks on as its upstream neighbours China and India kept up their efforts to build dams to unilaterally control the water flow in the trans-boundary river Brahmaputra, the lifeline of water supply during the dry season.

Accounting for 70 per cent of all natural water flow during the dry season, which covers winter and a part of pre-monsoon time, the Brahmaputra is essential for Bangladesh’s economic activities, which substantially depend on agriculture, sustaining millions of people fighting poverty tooth and nail.

China is actively pursuing the world’s single-largest hydroelectric project with plans to re-route 70 per cent of the Brahmaputra’s water to generate 60 GW of electricity, more than double the current installed power generation capacity of Bangladesh.

India is planning to dam the Siang River, a major tributary to the Brahmaputra, with nearly double the Chinese capacity to store water from the river to generate 11GW of electricity.

“The basic idea here is that the upstream countries will take away water by interrupting the Brahmaputra’s natural flow with promises to return it after meeting their own needs,” said Md Khalequzzaman, who teaches geology at the Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania.

Theoretically, Khaleq explained, the process of re-routing water by China meant building a dam, creating tunnels through hills and letting the water flow through gorges using its power to generate electricity.

International newspaper reports suggest that the re-routing could expand over a stretch of 50 km.

Little is officially known about the dams as upstream neighbours are reluctant to share reports of their projects’ feasibility studies or their environmental or disaster impact assessments.

“There is a high chance for India to divert water for irrigation following electricity generation,” said Tuhin Wadud, director of Riverine People, a civil society movement to restore and conserve rivers.

Tuhin’s apprehension is founded in years of India arbitrarily controlling water in the Teesta River, which was reduced into rather dry land, separated by occasional patches of shallow water, particularly during the dry season.

India also announced a plan to divert water from the Dharla River. Teesta and Dharla are two major Brahmaputra tributaries.

Water and river experts warned that Bangladesh could see the Brahmaputra flow dangerously decline before long.

“Bangladesh faces a very big threat. There is no reason to believe in the rhetoric used by upstream countries about fair use of water unilaterally taken away, interrupting natural river flow,” said Khaleq.

Called Yarlung Zanbo in China, the Brahmaputra rises near Mount Kailash in the Himalaya before entering India and then flowing into Bangladesh to sink into the Bay of Bengal covering a length of 2,900km and catchment of 5.83 lakh sq km.

The massive river, one of the largest in the world, is held sacred by many tribes in India. The river also flows along one of the world’s most active geological fault lines, where some of the world’s worst earthquakes occurred over centuries.

Communities’ resistance to the state’s move to interrupt the Brahmaputra dates back to the 1980s.

Building a mega-dam such as the one China is planning, dwarfing even the famous Three Gorges Dam, which reportedly slows down earth’s spin, in such a geologically sensitive area is considered by experts a bad idea.

International newspapers reported that the project will cost China $137bn.

The sheer size of the dam is so massive that it involves water falling down 5,000 metres, about five times the height of Bangladesh’s highest mountain peak.

Climate-induced rapid glacier melt, which recently burst more than one dam, heightens the risk of disaster manifold, experts warned.

Large dams also trap sediments, leading to riverbed degradation and soil fertility loss, river and environmental experts said, adding that interrupting natural water flow threatens to abruptly affect aquatic ecology and the delta-building process occurring through rivers carrying sediments.

Trans-boundary rivers in the 1960s used to carry to Bangladesh about two billion tons of sediments, which dropped to one billion tons lately, experts said.

“Brahmaputra flow contributes the most in preventing saline water intrusion in coastal Bangladesh,” said Malik Fida A Khan, executive director, Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services, a state-owned organization.

“Bracing for so many disastrous impacts requires good planning, which is denied by upstream countries refusing to share information on the proposed projects,” he said.

Bangladesh has no bilateral treaty with India or China about sharing water in the Brahmaputra River. None of the countries are signatories of the UN’s international watercourse convention.

Bangladesh’s request sent this year to China about sharing feasibility studies done on its massive dam failed to yield any result.

Joint Rivers Commission member Mohammad Abul Hossen said that they requested China two years ago to share any studies conducted on the potential impacts of constructing the dam without receiving any response yet.

“Dams, if properly operated in consultation with downstream countries, could be beneficial in terms of flood control,” said Hossen.

But experts are not so optimistic. They called on China and India for conducting a joint Strategic Environmental Assessment to determine the impacts of the proposed dams.

They also urged Bangladesh to become proactive, taking initiatives such as signing the UN’s international watercourse convention and working together with India to diplomatically put pressure on China against its potential unilateral control of common river water.

Bangladesh should also take the opportunity to highlight India’s arbitrary control of water on the Teesta River and the disastrous consequences the Farakka barrage in Ganges bore for downstream Bangladesh. Barring natural water flow resulted in increased erosion in the rivers’ banks as well.

Hundreds of families had to leave their ancestral homes behind or saw those get devoured during monsoon, when India releases water, often without warning. Fishermen lost their livelihoods following fish populations falling.

In 2020, the Lowy Institute, an Australian think tank, argued in a report that control over rivers rising from the Tibetan Plateau essentially gives China a ‘chokehold’ over India’s economy.