Price of Corruption in a Warming World

- Update Time : Saturday, November 8, 2025

—Kaniz Kakon—

It’s a beautiful day, and I cannot see it.” That quiet sentence could be the confession of our era. Bangladesh stands today at the intersection of light and blindness, a country radiant with potential yet dimmed by moral decay. For over a decade, it has been hailed as a global example of resilience, a nation that taught the world how to rebuild after disaster. But behind that narrative lies a quieter, more troubling story, one where the funds meant to protect the vulnerable against climate devastation have been quietly siphoned away. Transparency International Bangladesh recently revealed that more than half of the national climate fund, around Tk 21.1 billion, or roughly US $248 million, has been lost to corruption and mismanagement between 2010 and 2024. What was envisioned as a shield for the flood-displaced, the coastal poor, and the cyclone-stricken became, in many cases, a feeding ground for political influence and bureaucratic indulgence. This is not merely a question of theft; it is a question of vision. When the most climate-vulnerable nation on Earth allows its lifeline to rot from within, it signals something deeper than institutional failure; it signals the erosion of our collective conscience.

This erosion is not uniquely Bangladeshi; it is global, systemic, and devastatingly human. According to the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, global climate finance reached US$1.27 trillion in 2021–2022. Yet vast portions of this money, intended to fund mitigation, adaptation, and environmental restoration, have been misused or poorly tracked. The London School of Economics recently highlighted how climate finance flowing through forestry, energy, and mining sectors often disappears into networks of hidden contracts, inflated costs, and political patronage. And Transparency International’s 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index shows that over two-thirds of the world’s countries score below 50 out of 100 in ensuring integrity in public spending. In the global South, where vulnerability meets desperation, this moral collapse becomes catastrophic. When governments speak of “green transition” while quietly draining the very funds meant for it, the climate crisis mutates from an environmental challenge into a moral apocalypse. Bangladesh’s case is just one episode in a broader tragedy: a world that cannot tell the difference between building resilience and performing it.

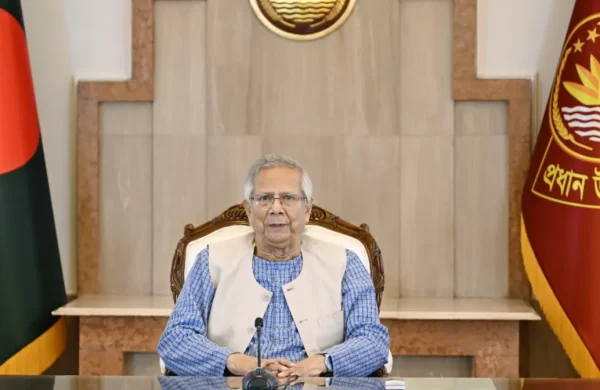

In Bangladesh, this blindness has become almost cultural. Politics has grown addicted to spectacle, to the visible over the virtuous. Grand inaugurations replace quiet accountability; televised development replaces transparent governance. We have learned to applaud infrastructure while ignoring injustice, to call a new highway progress while overlooking the hungry villages beneath it. The recent TIB report notes that over 61 percent of projects under the national climate fund were delayed or repeatedly reapproved without progress. Some never even began. Such waste doesn’t only weaken adaptation, it weaponizes despair. It teaches citizens that corruption is inevitable, that politics is merely self-preservation in the name of service. Even now, as Bangladesh transitions under a new interim government promising reform and renewal, there lingers a profound skepticism: after so many cycles of rhetoric, can integrity still survive politics? The truth is, without transparency, even noble leadership becomes another performance. Political vision, like eyesight, fades when it stops being exercised.

Globally, a few nations have started to reclaim that vision. Chile’s national transparency portal now allows citizens to trace every public environmental expenditure in real time. Rwanda mandates public disclosure of all climate-project beneficiaries, while Norway links its disbursement of climate finance to verified annual audits. These measures are imperfect but instructive; they remind us that sunlight, even partial, disinfects. Bangladesh could follow suit: digital dashboards for fund disbursement, community-based monitoring, independent evaluations, and mandatory publication of project results. The challenge, however, runs deeper than procedure; it is philosophical. It demands that politics rediscover its ethical imagination. The philosopher Iris Murdoch wrote that goodness is “a kind of attention”, to see, to notice, to care. The corruption of climate funds is, therefore, not just the embezzlement of money but the death of attention itself. We have stopped seeing those who depend on these resources: the char-dweller who loses his land each monsoon, the fisherwoman whose nets rot in saline water, the child who coughs through industrial air. Climate injustice begins when these people disappear from the political imagination.

So yes, it may be a beautiful day, the rivers shimmer, the delta glows, and promises of reform echo across the nation. But beauty without integrity is an illusion, and sunlight without vision is blindness. Bangladesh’s struggle is not simply to recover stolen money but to restore moral sight, to believe again that governance can be good, that care can coexist with competence, and that the measure of progress is not how much concrete we pour but how many lives we protect. The same challenge faces the world: global funds and summits mean little if they do not translate into justice for the vulnerable. If Bangladesh can make this pivot, from corruption to conscience, from performance to principle, it could yet lead by example, not in resilience born of suffering, but in honesty born of courage. Because the sky will remain blind until we learn to see not just the climate, but the human condition beneath it.

————————————————————————-

The writer is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Philosophy at IUBAT and currently on study leave, residing in Oslo, Norway