Are we trading away our privacy for comfort?

- Update Time : Saturday, April 5, 2025

—H.M. Nazmul Alam—

The revolution we once dreamt of is here. Once the stuff of science fiction, technology today pervades almost every corner of our lives. Smartphones that fit in our pockets now hold more computing power than NASA had during the Apollo moon missions. Artificial intelligence is writing poems, diagnosing diseases, and driving cars. Cloud computing, genetic databases, and the Internet of Things (IoT) have knitted themselves so seamlessly into our daily routine that we rarely stop to notice them anymore. Technology has gifted us with convenience beyond imagination.

But convenience comes with a cost. And perhaps the steepest cost of all is privacy.

In this age of hyper-connectivity, we need to ask ourselves a simple but profound question: does personal information even exist anymore? We unlock our phones with our faces, let Siri, Gemini, and Alexa answer our most personal questions, and eagerly pour the details of our lives onto social media platforms for a few fleeting moments of validation. Every click, every scroll, every heartbeat recorded by wearable tech is meticulously analysed and categorised—and often sold to the highest bidder.

An article in The Guardian published in 2018 revealed how Google collects various types of data about a user every day, including their precise location, browsing history, shopping preferences, social media habits, and even sleep patterns. Social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff, in her seminal book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, warns of a dangerous new economic order where “human experience is claimed as free raw material for translation into behavioural data.” Her conclusion is frightening: “If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.”

Governments are not far behind in this data-driven pursuit. Take the Chinese government’s social credit system, for example. Under this system, citizens are constantly monitored—both online and offline—and their actions are scored and ranked in a complex algorithm that determines whether they can travel, what kind of jobs they can apply for, and even whom they can marry. A late payment on a loan, spending too much time playing video games, or voicing political dissent online can lower an individual’s score, leading to severe restrictions in personal freedom.

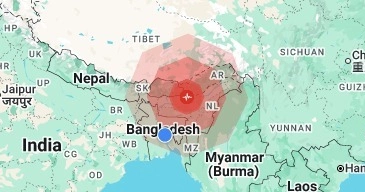

The United States National Security Agency (NSA) has long been accused of mass data collection and wiretapping, as revealed by whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2013. Closer to home in Bangladesh, questions around digital surveillance are becoming increasingly pressing. GPS tracking, biometric databases, facial recognition, and a growing network of CCTV cameras are becoming ubiquitous in cities like Dhaka and Chattogram. What began as tools to enhance efficiency, public safety, and security are inching ever closer to becoming tools of control.

This growing web of surveillance technology recalls philosopher Michel Foucault’s concept of the Panopticon, a design for a prison where inmates never know whether they are being watched, so they behave as if they always are. Foucault argued that the mere possibility of surveillance leads people to regulate their behaviour voluntarily. “Visibility is a trap,” he warned.

In the digital age, we may be constructing a new kind of Panopticon, where constant connectivity means constant observation. Unlike the inmates of the Panopticon prison, we have volunteered to enter the cell, bringing with us our smartphones, smartwatches, and smart home devices. We are living under what some call “digital feudalism,” where we trade away personal information in exchange for convenience, comfort, and social connection. As philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues in Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, “The neoliberal regime of self-optimisation and transparency makes the citizens complicit in their own domination.”

This dystopian future was anticipated long ago. In 1984, George Orwell envisioned a world where Big Brother watched everyone, everywhere, all the time. But our reality is more complex. We have welcomed Big Brother into our homes in the form of smart assistants and smart devices. In Brave New World, Aldous Huxley warned that people wouldn’t need to be oppressed by force, but would willingly surrender freedom in exchange for comfort and pleasure.

What does all of this mean for personal freedom? As Yuval Noah Harari observes in Homo Deus, “Once Big Data systems know me better than I know myself, the authority will shift from humans to algorithms.” Already, algorithms determine what news we see, what ads we’re shown, and what content gets prioritised on our feeds. The concern is that predictive analytics will not just predict our behaviour—but shape it.

If artificial intelligence can predict, with high accuracy, how we will vote, what we will buy, and even what we might be thinking, then how free are we, really? Will our choices remain our own, or will they be subtly nudged and manipulated by forces beyond our understanding?

Consider behavioural economist Cass Sunstein’s concept of the “nudge.” Subtle changes in how choices are presented can significantly influence decisions. In a world where data allows personalised nudges, the potential for manipulation becomes dangerously powerful. Who controls the data controls the narrative—and, by extension, human behaviour.

Despite this dystopian trajectory, all is not lost. Movements advocating for digital rights and privacy are gaining momentum. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has become a global benchmark for privacy protection. It empowers individuals to know what data is collected about them, how it is used, and to demand its deletion. Organisations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) continue to fight for internet freedom and privacy rights. In countries like Bangladesh, the conversation around digital privacy and cybersecurity is slowly beginning, though much work remains.

Technologists and ethicists are also calling for a “Privacy by Design” approach in developing new technologies—embedding privacy considerations into the architecture of digital systems, rather than treating them as an afterthought.

Some thinkers, like Jaron Lanier, advocate for a complete rethinking of the data economy. In his book Who Owns the Future?, Lanier argues for a system where people are paid for the data they produce, creating a more equitable digital economy.

As we stand on the threshold of a new digital age, we face a critical choice. Will we drift further into a world where privacy is a relic of the past, or will we fight to reclaim our autonomy?

Perhaps the question is not whether we can live without privacy, but whether we are willing to. What does it mean to be human if our thoughts, desires, and actions are constantly predicted, categorised, and commodified?

The poet Rumi once said, “Don’t you know yet? It is your Light that lights the world.” In a world obsessed with data and control, we must remember our humanity—the inner light that technology can never fully quantify or predict.

The tools of surveillance are already here. Whether we wield them with wisdom and care, or let them wield us, remains to be seen.

________________________________________

H.M. Nazmul Alam is an academic, journalist, and political analyst. He can be reached at [email protected].