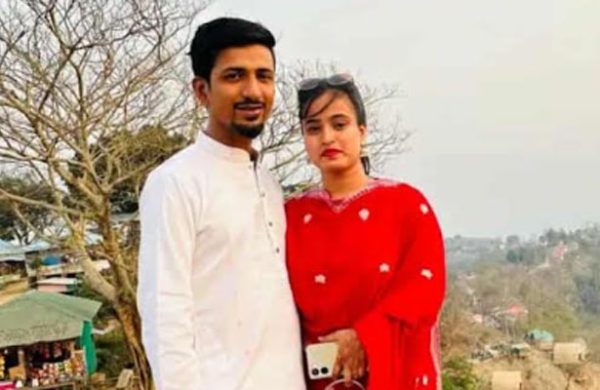

Bangladesh’s Manoshi clinches Mrs Universe Canada title

- Update Time : Tuesday, July 29, 2025

Entertainment Desk:

The indomitable artist placed runner-up at Mrs Universe Canada 2025, an achievement that felt less like a coronation, more like a reckoning. She was also named “Queen of Humility”, a title she wears with surprising delight. “I know it sounds ironic,” she laughed, “but that recognition reminded me that staying grounded is still something people notice and value.

This wasn’t Manoshi’s first appearance on a pageant platform. Back in Bangladesh, she reached the Top 20 in Miss World Bangladesh 2017 and was named runner-up at Face of Asia Bangladesh 2019. “Those experiences were incredibly formative,” she shared. “They built my confidence and helped build my presence.”

Her journey doesn’t begin in sequins and spotlights, but in a hill station boarding school in Kurseong, India, where at six years old, she was sent to chase the kind of education her parents could only dream of. “My dorm smelled of mothballs and eucalyptus,” she recalls. “We spoke in a collage of Hindi, English, and Bengali. I didn’t even realise how much I was learning just by listening.”

Coming back to Dhaka, however, was jarring. “I didn’t belong anywhere.” she recalled. Bullying, alienation, cultural confusion; it wasn’t until she entered North South University and shifted from Computer Engineering to English Literature that she found her footing. “Writing gave me the freedom to finally feel like I could exist in one piece.”

Manoshi’s debut book, “The Roles We Play”, is an unflinching examination of generational trauma within South Asian families, especially the kind passed down by women to women. “My mother’s English book was once burned by my grandmother because she hadn’t cooked dinner,” she said. “And yet my mother went on to become a professor, raise a family, and still carry the weight of those expectations. “I want other women to know it’s okay not to be a ‘Superwoman’,” she said. “We shouldn’t have to do it all to prove our worth.”

The pageant was simply a medium. “After becoming a wife, an immigrant, and someone who had disappeared into functional roles, the competition was a way to step out and say, ‘I’m still here. All of me.'”

As for the competition itself, it was by no means superficial. She trained for months, balancing workouts with workdays, revisiting her stage presence, picking up French classes, and relearning how to walk in heels she had stowed away years ago.

Her training was as much emotional as it was physical. She took up intermittent fasting, returned to the gym, and practiced public speaking. She also unpacked years of internalised self-doubt; tending not just to her posture, but to her past.

During the day, she works at the Ottawa Art Gallery as a lead venue coordinator, orchestrating exhibitions and community events. “I love what I do,” she said, without hesitation. “Art has its way of making people confront things they otherwise avoid; whether that’s grief, identity, or belonging.” Her colleagues, she said, were deeply invested in her journey, many of them following her competition updates with unfiltered joy.

In her off-hours, she builds systems of care for immigrant women — advocating for better access to mental health resources, legal support, and employment tools. “Everything I’m doing now is about creating visibility and stability for people who don’t always have it,” she added. “The glamour is incidental.”

Her involvement in the pageant has since taken a quieter, more community-focused direction. She is currently working on initiatives to support immigrant women, with a particular focus on improving access to mental health care, legal resources, and employment support. “It’s still early,” she says, “but this is where I want to keep building.”

“To anyone watching,” she says, “know this: your background doesn’t confine you. It completes you. And it’s never too late to come home to yourself.”