Dengue’s Deadly Grip Demands Healthcare Equality

- Update Time : Saturday, November 9, 2024

---Kaniz Kakon---

In the heart of Dhaka, a mother anxiously watched as doctors worked to stabilise her young son, who had just been diagnosed with dengue. Despite living in the capital with immediate access to private healthcare, the family’s journey to the hospital was marked by urgency and fear. If dengue could strike her family so intensely, she wondered how much harder it must have been for patients living in rural or semi-urban areas, where hospitals are not nearby, and reaching a large city for critical care is often a matter of life or death. Her story reflects a disturbing reality: in Bangladesh’s struggle with dengue, everyone is at risk, but those with fewer resources and limited access to healthcare face the steepest challenges.

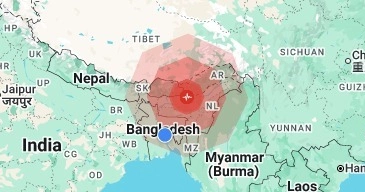

This year, Bangladesh has recorded over 68,000 dengue cases and 330 deaths (until morning 6 November), with the month of September alone seeing 80 fatalities. As dengue cases surge, Dhaka’s hospitals are operating at full capacity, yet patients from rural and remote areas are making their way to the capital, often travelling long distances in ambulances that lack proper medical equipment. This centralisation of healthcare places an overwhelming burden on Dhaka, while also creating a tragic healthcare disparity: families from rural areas, unable to access local care, are forced to wait longer for treatment and face lower chances of recovery. This issue highlights a critical gap in the human right to health, showing that for healthcare to be fair, every region needs the resources to manage disease outbreaks.

One perspective that illuminates this challenge is based on the theory of Positive Rights, which asserts that governments have a responsibility not only to avoid harming their citizens but to actively support and protect their well-being. This theory, central to human rights discourse, highlights that health is not just about the absence of disease but the presence of accessible, quality healthcare for all. In Bangladesh, a healthcare model focused heavily on Dhaka leaves other regions under-resourced and reliant on the capital, falling short of this positive rights obligation. From this perspective, the state should ensure that rural and low-income communities receive equal access to both preventive measures and responsive care, allowing each person to seek treatment when needed without unnecessary delays.

Dengue’s Deadly Grip Demands Healthcare Equality

The challenges are compounded by dengue’s changing behaviour, with symptoms now harder to detect until later stages. Early intervention is critical, yet awareness of early symptoms is low among many communities. For wealthier families, this gap can be bridged by private resources such as repellents, fumigation services, and early hospital access. For low-income and rural communities, however, a lack of awareness, access, and preventative measures leaves them exposed and less likely to detect the disease before it worsens. This situation underscores the health justice principle: that every citizen, regardless of income or location, should have equal access to healthcare resources, from preventive measures to effective treatment. Right now, this ideal is far from realised in Bangladesh, where inequalities in healthcare mean that poorer communities often face the most severe impacts.

Experts agree that overcoming this crisis will require more than just basic mosquito control campaigns. The Aedes mosquitoes that carry dengue breed in clean indoor water and bite during both day and night, making standard fumigation efforts insufficient. Effective campaigns must be localised and proactive, focusing on high-risk areas, and launching community-driven education to empower people with the knowledge needed to prevent infections. This means going beyond Dhaka and prioritising all communities equally. By upgrading district hospitals, establishing mobile medical units, and reinforcing healthcare facilities in semi-urban and rural regions, Bangladesh could ease the burden on Dhaka’s overwhelmed hospitals while providing crucial care closer to home. These measures would allow patients to receive early, life-saving treatment without travelling long distances.

We started with a story of a mother in Dhaka who, despite her proximity to healthcare, faced the terror of dengue. Let us now close with a contrasting story of a father of two children from a small village outside Chattogram. In his case, the family had no nearby private hospital, and reaching even a basic medical facility required over an hour’s journey. As his condition worsened, his family finally made the long trip to a hospital, only to find it overwhelmed and unable to provide urgent care. His tragic passing shook his community, serving as a painful reminder of the healthcare inequities that make geography and income big barriers to survival. His story is not just a statistic—it is a call to action, urging Bangladesh to close these gaps so that no family, urban or rural, wealthy or modest, has to face such preventable loss.

Bangladesh’s dengue crisis is a wake-up call to build a more inclusive, resilient healthcare system that serves all its citizens. This moment offers an opportunity to reshape healthcare policy, bridging gaps in access, strengthening local facilities, and equipping communities with the knowledge and tools to fight back. By investing in fairer, more proactive healthcare practices, Bangladesh can create a future where health crises do not hit some people harder than others, and where every family, regardless of its location, has an equal opportunity to survive and thrive.

_____________________________________

The writer is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Philosophy at IUBAT and pursuing a Masters in Human Rights and Multiculturalism at University of South Eastern Norway