Iran-Israel War: A Concern for Bangladesh

- Update Time : Monday, June 23, 2025

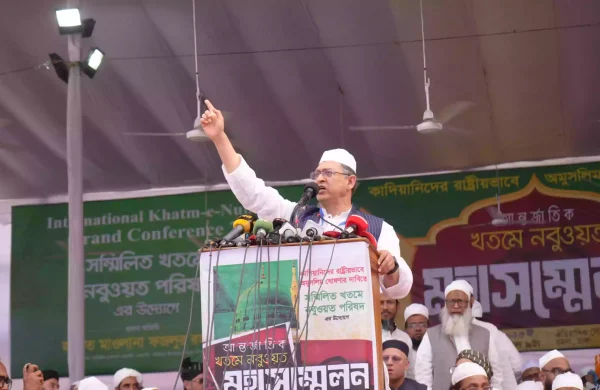

—Zubair Hasan—

As the Iran-Israel war intensifies, the critical question arises: does the United States truly understand the endgame of this escalating conflict? Only the U.S. has the power to restrain Israel, but the real concern is—will it choose to? Judging by history, the answer is likely no. The U.S. seems unwilling to learn from its past military ventures. It won battles in Afghanistan and Iraq, but ultimately lost the wars. There is a clear difference between winning a battle and winning a war. A battle is a single military engagement, a tactical episode. A war, by contrast, is a prolonged political and strategic struggle that requires not just battlefield success but sustainable outcomes. The U.S. won battles on the ground but lost the wider wars by failing to achieve any long-term political or strategic stability.

The United States invaded Afghanistan on October 7, 2001. At its peak, the war effort included over 130,000 troops from 50 NATO and allied countries, with over 100,000 American troops deployed by 2011. Yet despite this massive coalition and years of military presence, the U.S. mission ultimately ended in failure. According Iran-Israel War: A Concern for Bangladeshto the Costs of War project by Brown University, the financial cost exceeded $2.3 trillion. The U.S. lost 2461 troops in Afghanistan; its allies suffered more than 1140 casualties, including 457 British soldiers. Tens of thousands of Afghan civilians and troops also perished. After two decades of occupation, the Taliban not only survived but returned to power—stronger and more organised than ever.

The U.S. departure was nothing short of humiliating. On 30 August 2021, the last American soldier left Kabul. The world witnessed scenes of Afghan civilians clinging desperately to departing aircraft, the rapid collapse of the U.S. backed government, and the Taliban’s swift takeover. The images evoked memories of the fall of Saigon. It marked the end of a war that achieved very little but damaged America’s reputation deeply.

While the United States bled trillions in the Afghan mountains, China quietly advanced its influence. Beijing focused on infrastructure, trade, and global investment. China emerged as a financial superpower, free of war entanglements, and heavily invested in Afghanistan through the Belt and Road Initiative and lucrative mining contracts. Afghanistan is rich in rare earth elements and lithium—critical for green technology and electronic manufacturing. It’s China, not America, is now positioned to benefit from these strategic resources.

In Iraq, the U.S. failure was equally stark. The 2003 invasion based on false claims about weapons of mass destruction left hundreds of thousands dead and caused immense financial and human loss. Instead of reducing Iranian influence, the war opened the door for Tehran to expand its regional power. The chaos gave birth to the Islamic State (ISIS), a group that terrorised the region for years. The Iraq war, like Afghanistan, ended without meeting any of its original objectives.

Despite these lessons, the U.S. appears ready to repeat its past mistakes. As tensions flare between Iran and Israel, Washington risks entering another war without a clear endgame. Unlike the past, however, the geopolitical landscape has shifted. Any major confrontation involving Iran will likely become a prolonged, multi-front proxy war. China and Russia, although unlikely to intervene directly, will use diplomatic, economic, and intelligence channels to counterbalance U.S. influence. Even if Iran suffers militarily, the strategic victory may still belong to China and Russia, who seek to distract and exhaust American power.

The U.S. may initiate wars, but it has repeatedly failed to end them on its terms. Overwhelming military might cannot substitute for strategic clarity. In this new era, Washington is no longer the sole power on the global chessboard, and certainly not the most patient one. It is easy to start a war, but stopping it, especially one without a clear objective is an entirely different challenge.

This conflict is already causing significant disruptions to the global economy, especially in the oil market. Bangladesh, like many developing countries, relies heavily on stable energy prices. A prolonged conflict in the Middle East will keep oil prices volatile, worsening inflation and increasing our import bills. Our foreign currency reserves will remain under pressure, and the cost of energy subsidies will rise. At a time when Bangladesh is already struggling with post-COVID economic recovery and high import bills, this war could deepen economic vulnerability.

Furthermore, the impact of this war may extend into the domestic political landscape of Bangladesh. Anti-American sentiment is likely to grow among the general population, especially as Israel’s actions against Muslim civilians dominate global headlines. Many Bangladeshis view the U.S. as complicit in Israel’s aggression. This sentiment could influence public opinion and reshape political narratives in the coming months. Bangladesh is currently standing at a democratic crossroads. After enduring over 15 years of authoritarian-style rule under Sheikh Hasina, people are increasingly demanding political reform. The anti-American wave could feed into this movement.

Simultaneously, Bangladeshis may look more favourably towards China. China offers economic assistance without political conditions and is already a major trade and infrastructure partner. As public anger towards the U.S. rises, China may gain greater goodwill and business influence in Bangladesh. This shift would harm U.S. interests and reduce American economic leverage in South Asia.

In essence, this war is not just a clash between Iran and Israel. It is rapidly evolving into a global power struggle. It is a proxy war between the U.S.-led G7 bloc and the BRICS alliance led by China and Russia. In this context, Bangladesh must proceed with caution. Our policymakers, politicians, and civil society must closely monitor the conflict and its ripple effects. Bangladesh should not take sides in this great power competition. Instead, we must prioritise our national interest through an independent, pragmatic foreign policy. Strategic neutrality, economic prudence, and diplomatic balance should guide our decisions in this volatile geopolitical climate.

——————————————————-

The writer is a political analyst. Email: [email protected]