Padma peril: Incomplete embankment leaves thousands at risk as monsoon nears

- Update Time : Sunday, June 1, 2025

UNB

With monsoon clouds gathering on the horizon, families living along the vulnerable left bank of the Padma river, downstream of the Padma bridge are once again bracing for nature’s fury as the embankment that promises to protect them remains incomplete.

According to Engr Enamul Haque, sub-divisional engineer of the Bangladesh Water Development Board’s Munshiganj office, only 47.67% of the work has been completed so far.

Despite a riverbank protection project costing hundreds of crores launched nearly four years ago, thousands remain anxious and exposed.

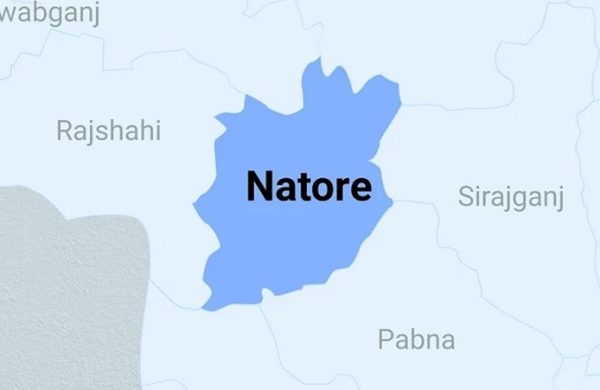

The project, which began in October 2021, was meant to bring long-awaited relief to erosion-prone stretches from Shimulia in Louhajang up to Dighirpar in Tongibari upazila.

But as the seasons have changed, little has changed for the people on the ground.

“I lost my land and my house to the river over 20 years ago,” said Kazi Babul of Gaodia village.

“Now I live just 200 metres from the river. Every time it rains heavily, we stay awake at night. If only the embankment work were done—we might finally get a peaceful night’s sleep,” he said.

The project, overseen by the Munshiganj BWDB office, covers 16.87 kilometres of riverbank.

Of this, 9.1 kilometres is designated for permanent embankment work, and 4.62 kilometres for precautionary protection, which involves placing geo-bags filled with sand in erosion-prone zones.

Initially slated for completion by October 2023, the project has seen both its scope and cost expand significantly.

The original budget was set at Tk446 crore for a 9.1 kilometre stretch. As the project’s length increased to 13.72 kilometres, the allocation rose to Tk470 crore.

It was revised again in December last year, raising the budget to Tk527 crore and the project length to 16.87 kilometres.

But the deadline has now been extended to September 2026. Yet progress remains painfully slow.

Engr Enamul Haque said the project is being implemented through 26 separate packages. “The total length now stands at 16.87 kilometres,” he said, noting this includes 1.3 kilometres of pre-existing embankment.

But 1.85 kilometres of vulnerable riverbank lies completely outside the project’s coverage, leaving residents in those pockets especially worried.

Golam Mostafa, a resident near the mouth of the Konkoshar canal, lives in one such area. “About 500 metres west of my house falls outside the embankment zone. Last year, waves caused serious damage during the monsoon. If we had permanent protection here, we would be able to live without this constant fear.”

Mostafa noted that over the last 25 years, the Padma has swallowed nearly 40 villages in Louhajang and Tongibari.

Around 50,000 families have lost their ancestral homes, farmland, and stability—becoming climate migrants within their own country.

From a distance, the Padma flows with majestic calm. But for those living along its left bank, it carries memories of broken homes and washed-away futures.

They have placed their hopes in the embankment project—a man-made barrier to halt a natural force. But until the work is finished, peace remains as elusive as dry ground during the monsoon.

Engineer Enamul said that action will be taken if erosion appears, whether along permanent or temporary stretches.

“We are monitoring closely. If any section shows signs of damage, we will respond immediately,” he said.