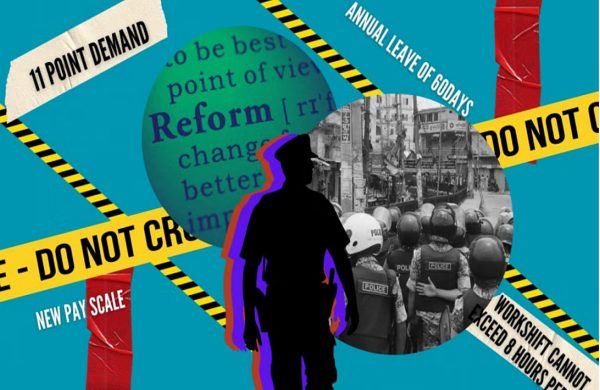

Police reform: Cosmetic change or systemic overhaul?

- Update Time : Friday, January 24, 2025

–Mohammad Jamil Khan–

In the months following the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s government on August 5, the police force has struggled to rebuild its reputation and operational capacity.

The force faced widespread criticism for its role during the anti-discrimination student movement, where the police were accused of indiscriminate shootings, killings, mass arrests, and torture.

The attacks on police stations and other establishments during the protests exposed the vulnerabilities of the force as well as the prevailing public anger towards it. For a week after the protests, the police were virtually absent from public view.

The interim government, upon assuming office, pledged to reform the police force. A reform commission was formed to draft proposals for these reforms, and given until January 15 to submit its report.

In the report, the commission recommended extensive measures to rein in the police and consider the abolishment of the Rapid Action Battalion. The commission also proposed that the police’s use of force against civilians will have to be the last resort and will have to be precise, proportional, and appropriate.

However, the home adviser Lt Gen (retd) Jahangir Alam Chowdhury on January 20 said that he is yet to get the police reform commission report. He did say that the recommendations are good, and they need time to implement the proposals. A change of mindset among the police would need more time too.

With the changes that have been implemented so far, the focus has been on superficial changes rather than addressing the structural issues that undermine the institution.

One of the most visible steps has been the decision to change the uniforms of police, Rab, and Ansar.

At a January 20 meeting of the Law and Order Advisory Committee, the government approved three new uniform colour schemes: “iron” for police, “olive green” for Rab, and “wheat gold” for Ansar.

This decision, which has been in discussion for the past few months, is being touted as a step to shift the mindset and behavior of law enforcement personnel.

On the change of the uniform, the home adviser said, “Alongside the uniforms, they [police, Rab, and Ansar] must change everything, their mindset, behavior, and conduct.”

However, while acknowledging these limitations, he admitted that many challenges remain, including the inability to replace damaged vehicles or adequately address infrastructure needs.

The focus on changing uniforms, however, has sparked criticism.

Experts and commentators argue that altering uniforms does little to tackle the deep-rooted problems within the force, such as corruption, human rights abuses, and a lack of professionalism.

BRAC Migration Program Chief Shariful Hasan in a social media post pointed out the misplaced priorities, emphasising that the funds used for new uniforms would have been better spent on structural reforms, advanced training, and rebuilding public trust.

Public discontent with the police stems not from their attire but from their perceived abuse of power and inability to protect human rights. This became painfully evident during last year’s protests, where police actions were widely condemned.

Uniform changes in the past—such as the shift to olive green in 2004—were often symbolic or practical adjustments. Yet, these changes failed to bring about meaningful institutional transformation. Critics fear the latest uniform update will follow the same trajectory, offering cosmetic changes while leaving systemic issues unaddressed.

The newly approved uniforms may give law enforcement personnel a refreshed appearance, but questions remain: will this lead to a realignment of priorities or just another superficial attempt to signal reform?

Without comprehensive efforts to address the root causes of public dissatisfaction, including accountability, training, and operational capacity, this move risks being seen as an exercise in optics.

True reform requires more than new uniforms.

It demands systemic changes that restore public confidence and enables the police to fulfill their duties effectively and ethically. Cosmetic changes might provide a temporary morale boost, but they cannot substitute for the deep, structural shifts necessary for meaningful transformation.

Policymakers and law enforcement leadership must focus on building an institution that is capable, accountable, and trusted. Uniforms are symbols, but they cannot mask the need for genuine reform.

The challenge is clear: will this be another missed opportunity, or can it be the starting point for holistic and lasting change?