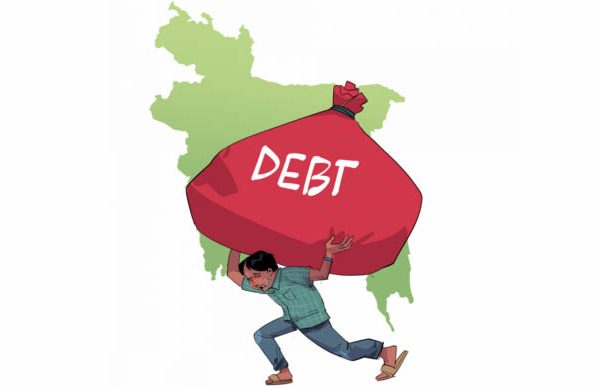

Rising debt signals warning for BD economy

- Update Time : Sunday, June 29, 2025

Staff Correspondent:

Bangladesh’s rising public debt is raising red flags among economists and policymakers, as the debt-to-GDP ratio has climbed nearly 11 percentage points over the past decade, reaching 37.62 per cent in the last fiscal year (FY 2023-24).

The ratio jumped rose to 36.06 per cent in the previous fiscal FY 2022-23 from 27.0% in FY2014-15, according to data from the Ministry of Finance (MoF), highlighting a growing reliance on borrowing to meet development needs and cover persistent budget deficits.

This steady upward trend is prompting calls for urgent fiscal discipline, strategic debt management, and stronger domestic revenue mobilisation to avert future financial stress.

Although the current debt level remains within the so-called “safe zone” under international standards, the pace of accumulation – fueled by mega infrastructure projects, shifting loan dynamics, and inefficiencies in debt use – has triggered concern about the country’s long-term repayment capacity.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) now projects that the ratio could reach 40.3 per cent by the end of 2025.

With a tax-to-GDP ratio hovering around just 7.4 per cent, Bangladesh continues to rely heavily on borrowing rather than internal revenue generation.

Economists warn that if this imbalance persists, particularly as more non-concessional loans mature, the country could face mounting pressure on foreign reserves and loan servicing capacity, threatening its economic stability.

Public debt, which includes both domestic and external borrowing, is becoming more central to how the government finances its development programmes.

Of the 37.62% debt-to-GDP ratio recorded in FY2024, around 21.52% originated from domestic sources, while 16.10% came from foreign lenders.

The total GDP of Bangladesh is officially estimated at US$461 billion at the end of FY 2024-25, meaning that the debt burden in both nominal and relative terms is becoming increasingly significant.

Economists say several factors are driving the surge in public debt: aggressive borrowing for large infrastructure or “mega” projects, a growing share of non-concessional loans, inefficient project execution, weak governance, global economic headwinds, and structural weakness in the revenue system.

A senior official at the Economic Relations Division (ERD) told The Financial Express that although Bangladesh’s debt-to-GDP ratio remains below the IMF’s general threshold of 55%, the country should not be complacent.

“We are still in a comfortable zone, but rising repayment obligations in coming years demand greater caution and planning,” he said. Economist Dr. Masrur Reaz noted that Bangladesh’s external debt has doubled in the past seven years, and the resulting rise in the debt ratio is due to indiscriminate borrowing without proper feasibility studies.

“There was excessive borrowing for mega projects by the last government, which sharply increased the debt-to-GDP ratio,” he said and warned that the risks are compounded by Bangladesh’s low tax base and weakening foreign exchange reserves. “We should not be complacent just because our ratio is below the IMF threshold. Our capacity for debt servicing is becoming fragile due to stagnant revenue collection and limited foreign reserves,” he said.

Dr. Masrur emphasised that the country’s debt burden is becoming more difficult to manage. “Neither our revenue nor our forex reserves are growing fast enough. This puts extra pressure on our debt repayment obligations,” he said.

If this trend continues unchecked, he cautioned, Bangladesh could face a serious debt crisis within the next five years. “Debt obligations could double, and if revenue doesn’t rise significantly, the country may find itself in deep trouble,” he added.

The IMF’s assessment reinforces this concern. While it considers a 55% debt-to-GDP ratio acceptable for many developing economies, it also warns that sustainability depends on individual countries’ macroeconomic conditions.