State-owned banks: Too big to fail or just too broken to fix?

- Update Time : Saturday, May 24, 2025

Staff Correspondent:

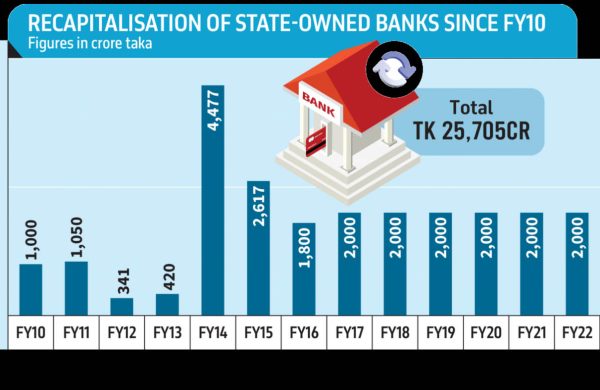

For years, the government has been on a life-support mission – pumping taxpayers’ money into state-owned banks to keep them afloat.

Between 2009 and 2024, under Sheikh Hasina’s regime alone, over Tk25,000 crore has been injected into these corruption-riddled banks. The rationale? Recapitalisation. The hope? Recovery. The outcome? A gradual deterioration in financial health, driven by politically motivated loans, poor governance, and the consistent failure of politically appointed boards of directors.

Let’s talk about Janata Bank – once a strong public sector bank that never required recapitalisation – turned into a crumbling edifice. By the end of 2024, its non-performing loans (NPLs) skyrocketed to a staggering 72% of total disbursements. Capital shortfall? Tk52,890 crore. That’s not just a number – that’s nearly one-third of the capital hole in the entire banking sector.

But Janata is not the outlier. It is the poster child of systemic failure. The other five state-owned commercial banks – Sonali, Agrani, Rupali, BASIC and BDBL – are not faring any better. On average, NPLs across these six banks stood at 48%. And let’s be honest – that number is mercifully cushioned by Sonali Bank’s relatively “modest” 16.4% NPL rate. Remove Sonali from the mix, and the average shoots closer to 60%.

Out of these six, only Sonali and BDBL show any semblance of capital adequacy – Tk82 crore and Tk575 crore in surplus, respectively. The rest are bleeding red ink. BASIC, Agrani and Rupali banks have severe capital shortfalls.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Bangladesh Krishi Bank, a rural credit institution, is staring at an abyss – a shortfall of Tk18,188 crore. Rajshahi Krishi Unnayan Bank follows with nearly Tk2,500 crore in deficits.

At this point, one might be tempted to compare the health of these institutions to the notoriously troubled banks under the control of Saiful Alam Masud of S Alam Group. And frankly, the comparison would not be unfair.

SO, WHAT WENT WRONG?

The government has recapitalised these banks in 13 of the past 15 years; however, the banking sector’s condition has regrettably worsened rather than improved. This paradoxical outcome stems from the inherent limitations of capital injections, which are insufficient to rectify deep-seated problems including dysfunctional governance, politically influenced lending practices, and the continued extension of credit to chronic defaulters often operating under modified identities.

ARE THESE BANKS TOO BIG TO FAIL? OR HAVE THEY SIMPLY BECOME TOO BROKEN TO SAVE?

“That’s the question policymakers must answer. Because taxpayers – who unknowingly finance this mess – deserve more than silence. They deserve accountability,” said Dr Fahmida Khatun, executive director of Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

Recapitalisation is not a uniquely Bangladeshi phenomenon, she said. It happens in many countries – but there, it is performance-based, tied to reforms and clear targets. In Bangladesh, however, it is little more than an annual ritual of fiscal bleeding – with no accountability, no improvement, and no return.

“This is not recapitalisation. This is a waste,” Dr Fahmida Khatun lamented. “These banks are not giving anything back.”

Her frustration is not misplaced. State-owned banks operate in a vacuum of accountability. Their boards – politically appointed – wield the power to approve loans, but rarely bear the consequences when those loans go bad. Instead, it is the executives who are blamed for the rising NPLs, while the real architects of the crisis remain untouched.

“The board sanctions the loans, but when the defaults pile up, it’s the executives who take the fall,” Dr Fahmida pointed out.

Her solution is as bold as it is necessary.

“The government must make a hard decision,” she said. “Shut them down – all but one. Let the state own and operate only a single bank.”

Syed Abu Naser Bukhtear Ahmed, chairman of Agrani Bank, said he opposed recapitalisation of state banks saying, “Good money should not go for bad money.”

STATE BANKS SERVE POWER, NOT PRUDENCE

The health of Bangladesh’s state-owned banks has deteriorated, with several lenders now buckling under the weight of loans extended to a handful of politically connected clients, insiders say. A closer look reveals a pattern of decisions driven more by influence than due diligence, threatening the stability of the financial sector.

Take Janata Bank, for instance. With a capital shortfall nearing Tk53,000 crore, nearly Tk40,000 crore of its loan portfolio is concentrated in just three corporate houses: Beximco Group (Tk23,000 crore), S Alam Group (over Tk10,000 crore), and Anontex (Tk5,000 crore).

Two of these borrowers – Beximco and S Alam – are reportedly struggling to sustain operations in the wake of political transitions, particularly due to their perceived proximity to the ousted Sheikh Hasina administration. With repayments drying up, the bank has been forced to classify these loans as non-performing, triggering massive provisioning requirements. But Janata simply does not have the liquidity to meet those obligations.

“Beximco has been banking with Janata for nearly 40 years. Their model was clear: pay interest, reschedule when needed,” said Md Abdul Jabbar, who served as Janata’s managing director from May 2023 to September 2024. “They were consistent with interest payments – sometimes Tk1,000 crore to Tk2,000 crore annually. Their exports were solid, and the bank was comfortable with that rhythm.”

But that rhythm has now been disrupted. Jabbar believes there’s still a path forward. “If Beximco returns to normal operations and becomes regular by paying down payment, half of Janata’s capital shortfall could disappear,” he pointed out.

Jabbar added that loan quality was significantly better when bankers made decisions based on sound assessment rather than external pressure. “Most politically motivated loans turned bad. Our internal assessments show loans based on professional judgement rarely fail.”

THE CRISIS IS NOT UNIQUE TO JANATA.

Agrani Bank, another state-owned lender, is grappling with a capital shortfall of around Tk5,000 crore. Its chairman, Syed Abu Naser Bukhtear Ahmed, said years of concentrated lending and suppressed reporting have exposed the bank’s vulnerabilities.

“Figures were kept hidden. Now that the real numbers are out, our NPL ratio has surged to nearly 40%,” Bukhtear told The Business Standard. “Unfortunately, many creditworthy clients were denied support over the last 15 years.”

Despite the alarming rise in bad loans, Bukhtear remains focused on preserving economic continuity. “We must keep factories running. That’s the only way banks will recover their money. Loans taken by state-owned entities have not been serviced for years – if those start getting repaid, the capital crisis could ease substantially.”

Dr Jamaluddin Ahmed, who chaired Janata Bank briefly in 2019-2020, offered a more systemic diagnosis: “NPLs are high in state banks largely due to political lending. Many board directors lacked both skills and clear responsibilities.”