To solve the Rohingya crisis, we must address the root causes

- Update Time : Tuesday, February 4, 2025

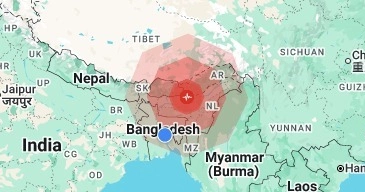

—Dr Mohammad Zaman—

The Rohingya crisis continues to mystify everyone with its uncertainties. In 2017, close to a million Rohingya people took refuge in Bangladesh over a period of only one month after a most brutal genocide and violent exodus in recent history. The influx of refugees continued in October-December 2024 due to the rise in armed conflicts between various armed groups and the military junta, as well as the impacts of the long-running brutal civil war inside Myanmar. Amid this, the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar refugee camps still hope to return to their homes in northern Rakhine—their old heartland in Myanmar.

The renewed violence has worsened the already precarious situation in Cox’s Bazar camps. Last year alone, according to one source, armed groups such as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO), and the Arakan Army (AA) recruited an estimated 5,000 men from the camps in Cox’s Bazar to fight against the Myanmar military. The radicalisation inside the camps, the increase in criminal gang activities, the targeted killing of camp leaders by opposing militant groups, and the continued cycle of violence have led to a significant deterioration of safety among the Rohingya refugees. To add to this, the renewed fighting between these armed rebel groups and the Myanmar junta has further pushed back any potential repatriation plan due to the lack of peace and stability inside Myanmar.

Given this situation, can we ever find a viable solution to the Rohingya crisis? Is there any pathway to resolve the crisis with accountability and justice for all? And who will find it?

To do this, we need to look back and understand Rohingya history. The armed struggles inside Myanmar and the demand for Rohingya autonomy and rights clearly establish that the crisis is not just a current humanitarian issue but also a political one, long rooted in Arakan’s history. In recent weeks, the AA has taken full control of 14 out of 17 townships, including Maungdaw near Teknaf, from the Myanmar military junta. Armed fighting still continues to capture the remaining government-held territories in Rakhine. In the process, many coerced Rohingya conscripts to the Myanmar Army have been killed or captured, further entangling the displaced people in a war they did not initiate. Any resolution of the crisis must understand and address both the political and humanitarian aspects.

Many people tend to think that the Rohingya crisis is a 21st-century issue. On the contrary, it encapsulates centuries of historical marginalisation, ethnic conflict, and geopolitical intricacies. The Rohingya have a 200-year history, starting from the violent occupation of the Arakan dynasty in 1784, which gradually evolved during the pre- and post-colonial periods in Burma. Their identity has been under sustained attack by the military and the Buddhist civilian majority through genocidal campaigns aimed at erasing their shared history and culture over the years. The 1974 constitution and the census that preceded it marked the clearest breaking point when “Rohingya” was replaced with “Indian or Pakistani” and later by “Bengali” among “non-indigenous or foreign races.” This was followed by the adoption of the discriminatory Citizenship Act of 1982. The decades of brutal oppression that followed forced many Rohingya to flee the country over the past 40 years. on Tuesday four out of every five Rohingya live as refugees in countries across the region and around the world. Those still inside Myanmar are in camps in Buthidaung and Maungdaw or under military surveillance.

The magnitude and duration of this crisis require a comprehensive understanding of the underlying causes, an assessment of humanitarian interventions, and an examination of avenues for justice and reconciliation. Myanmar, Bangladesh, and the regional and international communities must address the root causes of the Myanmar crisis, including the long-standing discrimination and statelessness faced by the Rohingya. Any measures short of that would not be sufficient to resolve the crisis and facilitate the return of the Rohingya to their homeland.

While the repatriation of refugees is urgently needed to reduce the long-endured burden on Bangladesh, the government should work more closely with countries having significant influence on Myanmar—for instance, India, China, Korea, Singapore, and Japan—to apply pressure to ensure accountability and to provide local autonomy for the Rohingya in the Rakhine state, aimed at creating conditions for their return with dignity and rights. The US government should also support efforts to hold Myanmar’s military leaders accountable through the ICC. The second Trump administration has an opportunity to reflect on its past policies and take bold steps towards a more just and lasting solution. The Rohingya crisis and displacement should be of concern due to the strategic security interests of the US in the Southeast Asia region.

What is required now is to keep the global focus alive on the Rohingya crisis to find a durable solution. The international community must also increase humanitarian aid and assistance to support the refugees and improve living conditions and rights in the refugee camps in Bangladesh. The Rohingya people have been waiting and watching the indifference and inaction of the world for years. They are hoping for an early, safe, voluntary, and dignified repatriation.