Untold realities of remittance warriors

- Update Time : Tuesday, December 17, 2024

TDS Desk:

When Mizanur Rahman left Bangladesh for Saudi Arabia over two decades ago, his goal was to make a fortune and support his family and siblings. But during his stay abroad, he lost all contact with his family and as an undocumented migrant, life was not easy.

Upon landing in Bangladesh last year, he could not even tell where he was headed. His mental health appeared fragile — he frequently struggles with memory lapses and has difficulty articulating full sentences, pausing often to find the right words.

In the beginning, as he had faced issues in managing a job in Saudi Arabia, he hid for a while. At that point, he lost contact with his family. The jobs he managed later were barely enough to survive on. He also got into a tragic accident there and did not receive proper treatment.

After 22 years, Mizan was finally rescued by a joint effort between police and a team from BRAC’s migration programme. He is still undergoing treatment in his hometown, Badarkhali in Chakaria, Chattogram and could not talk to us.

“When my brother left, I was a kid. I never heard from him again. When we reunited, he could not recognise me. In fact, he still forgets at times that I am his brother,” said Rezaul Bhutto, Mizanur’s younger brother.

Today, Mizanur is in his late 40s, unmarried, with no savings and severe physical and mental health issues.

There is no exact data on how many Bangladeshi migrants have gotten lost or gone missing abroad, as these incidents are often underreported or occur during informal migration. However, challenges such as detentions, deportations, and exploitation abroad are significant.

A recent study by the Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU) highlighted that many Bangladeshi migrants return prematurely due to job losses, employer misconduct, or inadequate working conditions.

Abdul Jabbar, who also returned last year from Pakistan after 35 years of no contact with his family, comes from Dudhal village in Bakerganj, Barishal and once owned a rice mill.

After selling the rice mill, he handed over all the proceeds to a broker with dreams of migrating to Iran in 1988. The broker attempted to send him to Iran via India and Pakistan, but he was stranded in Pakistan. Without proper documentation, he was imprisoned.

Jabbar was able to send a few letters to his family in the first year, but later, lost contact. His last letter was written in Urdu and nobody could interpret it.

Last year, his family reached out to the BRAC Migration Programme and gave them whatever information they had about him. They requested that they bring him back.

After over three decades, when he finally returned, holding a Pakistani passport, he had lost the ability to speak Bangla, his native tongue.

“I was born three months after my father left for Iran. I never saw his face or heard his voice. When I was a kid, every time I saw a plane soaring through the sky, I would wish, with all my heart, that my father was on it, finally coming back home,” said Kamal Hossain, the youngest son of Jabbar.

Abdul Jabbar has two more children. When he left the country to go to Iran, his eldest son, Awal Akon, was just three years old and his daughter, Nupur, was only two. His wife never remarried and she was diagnosed with cancer five years back.

“This is a bittersweet chapter for all of us. I am grateful that we are united now,” added Kamal.

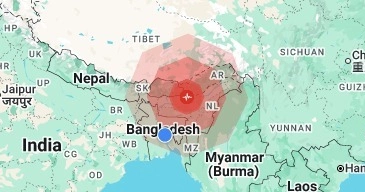

Bangladesh now stands as the sixth largest manpower exporter, with more than 10 million of our migrants working all over the world, according to government data.

“The actual figure likely exceeds 10 million, but we lack the means to track those who leave through informal channels. This makes comprehensive data collection difficult,” explained Shariful Islam Hasan, associate director at BRAC.

“Additionally, Bangladesh is the seventh-largest remittance-receiving country globally. While this sector continues to expand, the welfare of the individuals driving this growth often goes unnoticed and neglected,” he added.

Shariful further pointed out that Bangladesh ranked among the top countries with undocumented migrants attempting to reach Europe via the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR) for the last couple of years.

“This desperate journey is taken by many in search of a better life, but it comes with great personal risk,” he said.

A large number of Bangladeshis are also returning. Since 2008, nearly a million Bangladeshis have faced deportation for various reasons, mostly from the Middle East.

Shariful suggested establishing a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) at the airport to address the challenges faced by returning migrants.

“These individuals often come back in varying mental and physical conditions — some having endured abuse, exploitation, or torture, while others suffer from severe health issues. There are cases where individuals have lost their memory and cannot recall their families or locations. They require tailored support. Our airports should have dedicated sections and infrastructure to handle these cases sensitively and efficiently,” he stated.

Shariful mentioned another migrant named Abul Kashem, who returned from Saudi Arabia after 25 years with a travel pass but could not find his family or address because of his mental trauma and sickness. Later airport authorities referred him to BRAC.

Abul Kashem mentioned several addresses, including Halishahar, Hathazari and Nayabazar in Chattogram, during the search for his family. BRAC workers visited these areas to gather information and put up posters in visible locations. He was sheltered at the BRAC Migrant Welfare Centre during the search period.

These posters eventually caught the attention of Abdus Sabur, the councillor of Ward 25 of the Chattogram City Corporation. Sabur recognised Kashem and reached out to his family. After confirming the connection, BRAC facilitated the reunion by handing over Abul Kashem to his family in Dhaka last year.

“Such efforts should be systematic, involving coordinated actions from both government and non-government entities to ensure these individuals are reintegrated with dignity and support,” Shariful concluded.