Will disarming a ‘distressed’ police force shatter its capability?

- Update Time : Wednesday, June 11, 2025

TDS Desk:

The interim government’s recent decision to withdraw lethal weapons from Bangladesh Police has raised serious concerns among rank-and-file officers, many of whom see this as a move that could irreparably weaken an institution already reeling from the July Uprising.

Several officers, speaking on condition of anonymity, interpreted the decision as a deliberate attempt to a force already “distressed” and demoralised by the violent July mass uprising. They fear this step could leave them exposed and effectively “incapable” in the face of escalating threats.

The government has yet to spell out how the disarmament will be implemented despite far-reaching implications. But officers in the field insist that it is not the presence of weapons that leads to abuse, but political interference and the absence of proper oversight.

While critics of police brutality have long called for reform, many officers argue that misuse of lethal weapons is a governance issue, and not a logistical one.

Field officers argue that political interference and the absence of proper oversight, not the presence of arms, that lead to abuse.

“If police are allowed to operate by the book, there is no risk of misuse,” one officer told bdnews24.com. “Problems arise when they are instructed to act outside the law.”

Former Inspector General of Police (IGP) Mohammad Nurul Huda echoed this sentiment.

“Weapons aren’t the problem. The problem lies in their overuse–something that has political roots,” he said.

“Misuse can be prevented through proper supervision, control, and management.”

“Police lost confidence after the July Uprising,” said one officer who wished anonymity, “and now, if they are stripped of their weapons, they will be rendered totally ineffective.”

JULY UPRISING AND THE RECKONING THAT FOLLOWED

The decision to disarm police follows the bloodshed and repression associated with the July Movement, a mass protest that erupted nationwide and led to violent clashes between demonstrators and law enforcement.

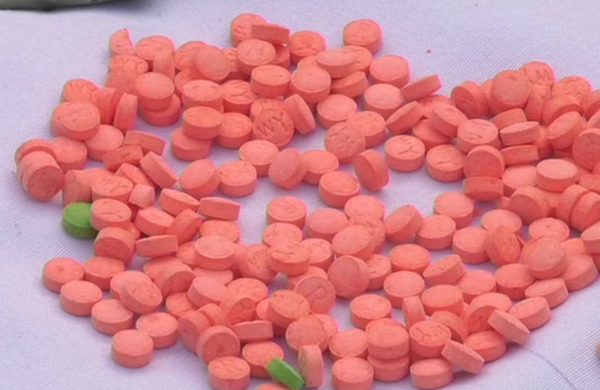

According to a UN report based on “dependable sources,” more than 1,400 people are feared to have been killed between Jul 1 and Aug 15, many by lethal weapons fired by police and other law-enforcing agencies. Thousands more were injured.

Following the collapse of the Awami League government on Aug 5, police stations across the country came under attack. Dozens were torched and vandalised. Police claim that at least 44 of their personnel were killed during the unrest.

The violent fallout deeply affected the morale of officers. For weeks, law enforcement activity slowed to a crawl, and the consequences are still being felt.

The interim government has since initiated legal proceedings against former prime minister Sheikh Hasina, former IGP Chowdhury Abdullah Al Mamun, and others on charges of “crimes against humanity” during the uprising.

A SHIFT IN POLICE POWER

On May 12, the issue of police armament came to the fore during the ninth meeting of the Advisory Committee on Law and Order.

Home Affairs Advisor Jahangir Alam Chowdhury announced the new policy: “Police should not carry lethal weapons anymore. They have to return the weapons,” he told reporters following the meeting.

When journalists asked how police would manage operations without such weapons, he clarified: “The APBn [Armed Police Battalion] will retain lethal weapons. For general operations, they are not required. Rifles will still exist—but not for every unit or deployment.”

The following day, IGP Baharul Alam also spoke to reporters.

“What the home ministry meant is that rifles capable of causing fatalities, those that fire live bullets, should be avoided. In principle, we believe police should not be a ‘killer force.’ Shotguns should be enough, that’s what the public expect.”

He added, “We will discuss it further with all stakeholders before reaching a final decision.”

A FORCE IN DISBELIEF

At the field level, the reaction was swift and bitter.

The statements sparked immediate backlash among rank-and-file officers, especially those who had been on the frontlines during the July unrest.

Many officers said the police already lost public confidence during the July Movement. Now, removing their weapons would render them “totally powerless”.

They argue that removing their arms is not only impractical but dangerous, both to them and to the public.

At present, assistant sub-inspectors to inspectors are issued personal pistols. Officers serving as bodyguards also carry sidearms. Constables are usually armed with shotguns and, in some cases, Chinese-manufactured Type 56 rifles, which are functionally equivalent to AK-47s.

One officer explained the typical arms distribution during a riot control operation.

“In a 20-member riot team, four carry shotguns, four have gas guns, four carry sticks and shields, and a maximum of four are armed with Chinese rifles. Two are tasked with arrest duties and carry handcuffs and batons. Two others handle sound grenades.”

He clarified that this level of armament is reserved for high-risk deployments.

“When providing security at a wedding or concert, no one carries Chinese rifles. That’s common sense. But for riots or unrest, it’s essential.”

He warned against applying European policing models to Bangladesh.

“This might work in Europe, not here. Without arms, patrol teams will get mugged. How can we provide security to others if we can’t protect ourselves?”

“Even now, criminals throw crude bombs at us. If they find out we’re unarmed, we’ll be their prime targets. Then you’ll be writing headlines every day about police being killed.”

LAWFUL USE OF FORCE

According to one officer, the law permits police to fire their weapons under four specific circumstances:

- When their own life is in danger

- When the life of another is threatened

- When there’s a risk to police property

- When there’s a threat to public or government property

“In spontaneous threats, we don’t need prior permission. But in planned riot situations, yes—a magistrate must approve it,” he explained.

“It’s up to the police to judge when to escalate force.”

He added, “You’re arming the Narcotics Control Bureau, but want police to patrol without weapons? That’s like turning us into village watchmen. Criminals won’t fear even DMP officers.”

POLITICAL ABUSE OF POWER

A superintendent working in Barisal Division pointed out that upper-level control of weapons is ineffective without political reform.

“In countries like ours, political interference is constant. The misuse of force doesn’t originate in police, it’s orchestrated from above.”

He noted that many officers received state awards for staging so-called “crossfire” incidents over the past 15 years.

“Enforced disappearances, crossfire killings, these were tools to suppress political opponents and petty criminals.

“The moment the political order changed, crossfire stopped—remember how it vanished after Army officer [Retired army major Sinha Md Rashed Khan] was killed in Cox’s Bazar?”

MORALE IN CRISIS

An additional superintendent of police, transferred from the Dhaka Metropolitan Police after Aug 5, said: “The shock of the July Movement shattered morale. Officers are afraid to act. Any incident, they push it upstairs.

“If we also take away their weapons, the night patrols will stick to the station, waiting for security assurance.”

He described how the criminal landscape has shifted since August.

“We’re now arresting thugs who used to drive rickshaws or work in shops. They fought us in July and realised there’s no crossfire, jail time is short, and bail is easy.”

“Now they kill over petty disputes. If they know police only have sticks and shotguns, they won’t hesitate to hack officers to death.”

THE WEAPON AS AUTHORITY

Former IGP Nurul Huda believes the government may be planning a strategic transition, but warns against unrealistic assumptions.

“If lethal weapons are withdrawn, what replakhes them, sticks? Tear shells? That won’t be enough to disperse mobs or confront organised criminals.”

He reiterated the symbolic and practical power of arms.

“Weapons are the symbol of police authority. The question is not whether force is legal, it’s whether its use is regulated.”

“People use weapons, they don’t operate by themselves. The problem is political misuse, not the weapons themselves.”

He called for a gradual, realistic reduction in arms.

“This must be a phased plan rooted in our own context. England has weapons too—but in specialised units with strict oversight.”

“In Bangladesh, weapons make people fear police. That fear underpins law enforcement. Without it, crime prevention becomes extremely difficult.”

APBN VS GENERAL FORCE

The home advisor suggested arming only the APBn. Huda disagrees.

“The APBn is just one of several police units, and it isn’t present everywhere. Assuming only APBn can use weapons is impractical.”

“If you’re trying to control 300 people armed with sticks and your officers have nothing, what then? These are ground realities.”

He urged the government to involve field-level officials in policy discussions.

“We need to reduce the use of lethal weapons without compromising law enforcement. It’s about finding balance.”

(Source: bdnews24.com)