Will they ever return? Families refuse to give up on disappeared loved ones

- Update Time : Thursday, August 29, 2024

TDS Desk:

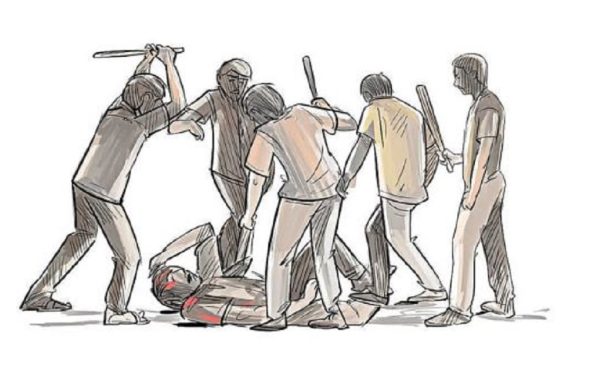

Ismail Hossain was the main breadwinner for his family of four, which includes his wife and two children. He was also the de facto guardian and provider for 22 people of his extended family — two widowed sisters and their eight children, one of his paralysed brothers and his family, and his paralysed mother — until 19 June 2019, when he was abducted.

Nasreen Jahan Smrity, Ismail’s wife, suspects that an officer of the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) abducted him due to a personal grudge.

“My husband was a BNP leader, but that officer did not abduct him for his politics, rather out of previous enmity,” Nasreen said.

“We have all been helpless since he was taken. My husband’s bank accounts could not be accessed. I went to every bank with my kids, but they refused to release any money because I couldn’t provide a death certificate,” she explained.

Nasreen once led a comfortable life with her husband’s income as a businessman, and her own as a teacher. However, after her husband’s disappearance, she and her family faced not only economic hardship and mental trauma but also regular harassment, including the tailing of their daughter, from Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and Detective Branch (DB) personnel.

Relentless search for her husband has so far yielded no results, and Nasreen believes RAB’s involvement in the disappearance is why her family remained under constant scrutiny by law enforcement agencies.

“Our life is now filled with sorrow. My daughter used to go to school by car, but now she walks to college. I give her some money for transport, and she walks the rest of the way. There are times when I don’t even have Tk2,” Nasreen said. “In those moments, I just look at the sky and wonder why we have to endure such pain when we have done nothing wrong. Allah must have something good in store for us.”

Like Ismail, hundreds of people became victims of enforced disappearance during the last 15 years of the Awami League’s authoritarian regime.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) reports that Bangladeshi security forces have committed over 600 enforced disappearances since 2009. While some of the disappeared were later released, produced in court, or claimed to have died in crossfire, many still remain missing.

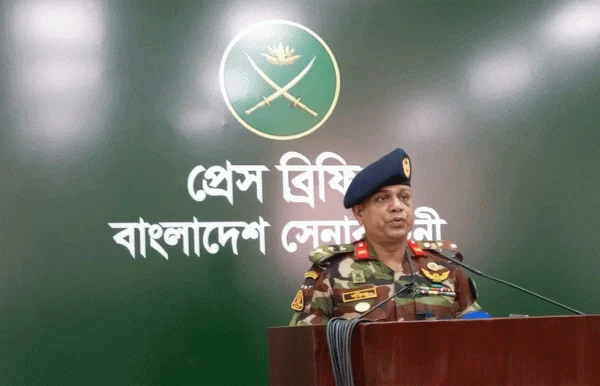

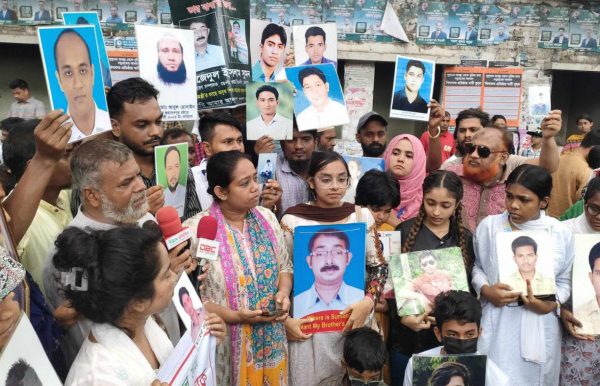

Mayer Daak, a platform organised by families of enforced disappearance victims, has campaigned for the return of their loved ones for several years. After the fall of Hasina’s regime, they sent a list of 158 missing people to the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), the intelligence agency of the Bangladesh Armed Forces.

Since the fall of Hasina, only three victims of enforced disappearance have returned alive: Michael Chakma, Mir Ahmad Bin Quasem, and retired Brigadier General Abdullahil Aman Azmi.

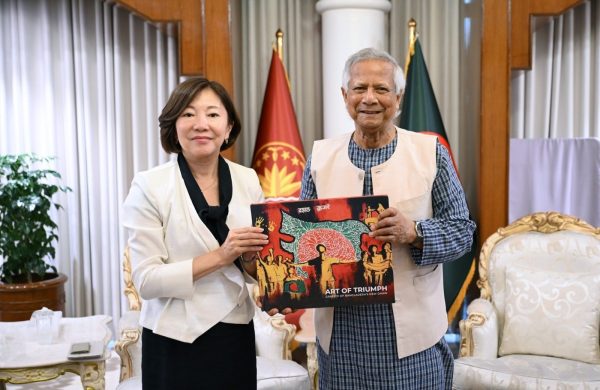

However, the interim government led by Dr Muhammad Yunus has decided to join the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED) and has established a five-member inquiry commission.

This commission is tasked with identifying and locating individuals who were forcibly disappeared by various intelligence and law enforcement agencies between 1 January 2010 and 5 August 2024.

Mayer Daak coordinator Sanjida Islam Tulee emphasised the need for a transparent investigation process, urging that the report should not conceal any findings. She also called for a mechanism to allow victims to submit evidence.

“We want a complete and transparent picture of what happened,” said Nusrat Jahan Laboni, an activist at Mayer Daak.

Kaniz Fatema, sister of disappeared Chhatra Dal leader Samrat Mollah, is happy that a commission has been formed.

“We don’t want much from the commission. All we want to know is if they are alive. Above all, we hope our loved ones are still alive, but if they are not, we ask the commission for justice,” Fatema said.

Samrat, the backbone of his family, managed their store and provided for his ageing father and siblings. As the organising secretary of Sutrapur Thana Chhatra Dal, Samrat was a key figure in the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

On 28 November 2013, while visiting a friend in prison, Samrat and four others were detained by DB.

Witnesses saw him being blindfolded and taken away, but while three of the detainees were later released, Samrat and another leader, Sohel, remain missing. Despite desperate attempts to file a case, the family faced resistance from the police due to Samrat’s political involvement.

“We want exemplary punishment so that no one in Bangladesh dares to commit such heinous crimes again. The mental trauma our families endure is beyond description; I doubt even death causes such pain. We have faced harassment in every aspect of our lives — social, financial, and legal.

“Finding a place to rent was difficult due to rumours about my brother, and marrying off my sisters was a challenge. Back then, people didn’t fully understand enforced disappearances. Many thought my brother might have been a terrorist or done something wrong,” Fatema further said.

Jamaluddin, father of Ishrak Ahmed who was abducted from Dhanmondi in 2017, also expects justice from the commission.

“We are hopeful we will get justice from the commission,” Jamaluddin said.

Nasreen Jahan does not know if her husband is alive, but her children are waiting for their father.

“My daughter told me the other day, while I was cleaning, not to throw some papers away because when Baba returns, he will look for them. This confidence of my daughter in her father’s return makes me hope that the commission will act so that her belief remains true. I also hope they will help us regain access to our bank accounts,” Nasreen said.

“When my children ask me if their father is alive, I have no answer. I seek an answer through you. If he is alive, please release him; if he is not, please tell us when and how he was killed. I hope the commission will provide answers for many other families like ours. At least inform us so we can organise a funeral,” she added.